Three days after a tsunami hit Japan's Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, South Korean President Lee Myung-bak was celebrating. It was March 14, 2011, and he was in the United Arab Emirates, in a dusty stretch of desert 30 miles (48 kilometers) from the nearest town. Lee was presiding over a groundbreaking ceremony for a construction project that the two countries said marked the beginning of a "hundred-year friendship ." An entourage of South Korean officials in dark suits and Emirati leaders in flowing white robes toured the scene. Later, Lee and United Arab Emirates Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed smiled and posed for photos on a red carpet.

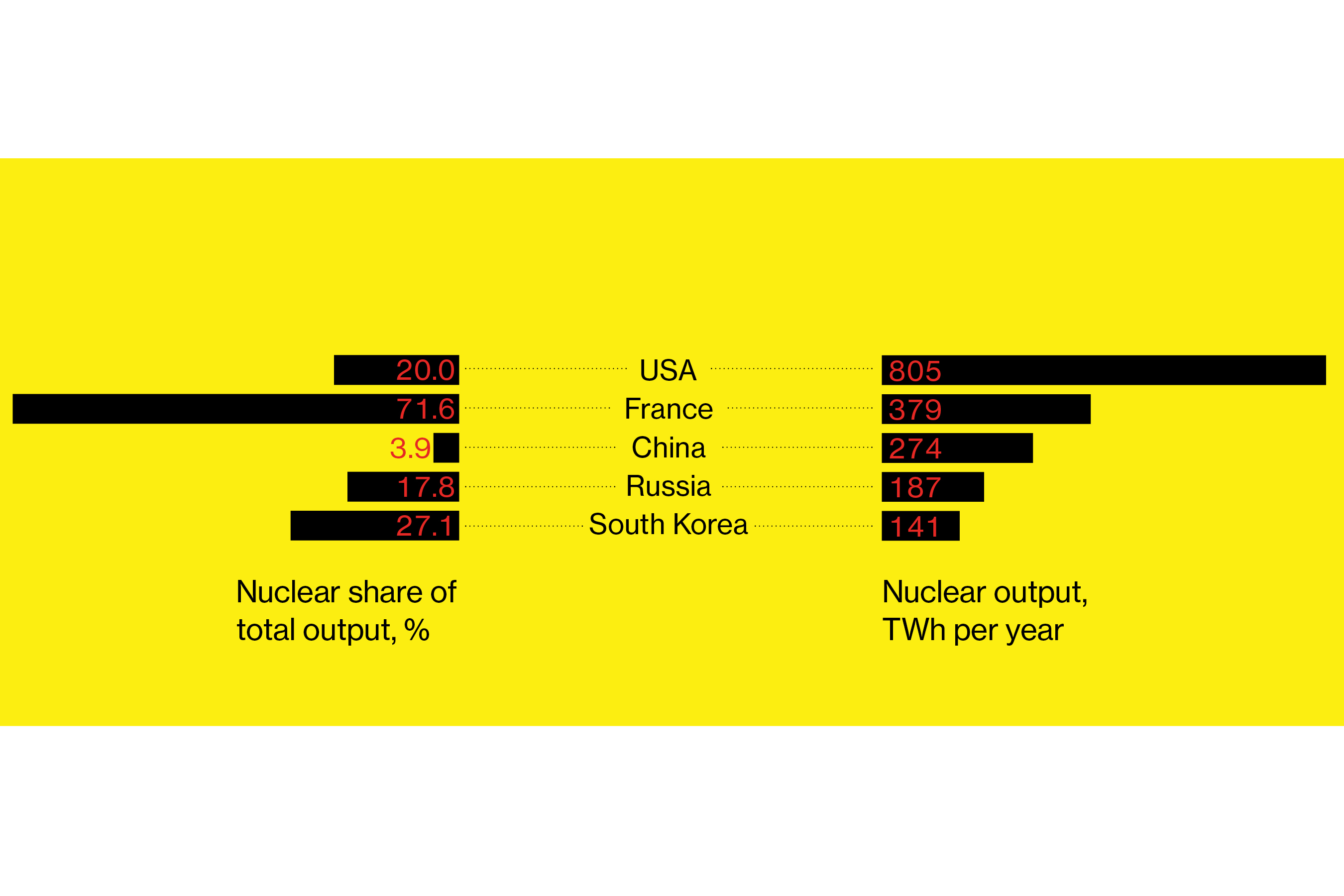

Two years earlier, a South Korean consortium had won an $18.6 billion (€16.584 million) contract to build four nuclear reactors on the land where Lee's ceremony took place, at the time the largest reactor deal in history. history. The plant, called Barakah, which is an Arabic word meaning 'divine blessing', was a personal triumph for Lee, who reportedly sealed the deal with a nerve-wracking 11-hour phone call to bin Zayed, and a victory for his country. whose Korea Electric Power Corporation, Kepco, led the bid and won against a more experienced French rival. It was a great achievement for the underdogs. A small resource-poor country that relied heavily on imported energy, South Korea began its nuclear program in the 1970s by buying reactors under turnkey contracts from Canada, France and the United States. But Kepco and its nuclear subsidiary, KHNP, quickly developed their own model based on an American design. The first self-created reactor was operational in 1995, and more soon followed. Over time, South Korea, which is about the size of Indiana, USA, became the country with the most reactors in the world , with 23 reactors providing about 30% of its total electricity generation. The Emirates had been impressed.

However, in the case of the Emirates, there was more at stake than South Korea's national pride. What this country was doing could help solve the climate crisis. Although renewable energy production has grown dramatically, many scientists, engineers, and environmental activists believe that the nuclear power system is the only truly scalable alternative to fossil fuels. But over the years, the high capital costs, uncertain returns and safety concerns associated with nuclear power have discouraged investors and led governments to turn to cheaper and dirtier fuel sources. such as coal and gas.

The French state-owned company Areva, for example, had a project in Finland that was already billions of dollars over budget and years behind schedule. The $6.8 billion Watts Bar Unit 1 reactor in Tennessee had taken 23 years to complete, and cost more than 18 times its original price of $370 million ( almost 330 million euros). Areva had submitted a bid for the Barakah project, but its $36bn (more than €32bn) bid was nearly double Kepco's. The Korean offer reignited hope that nuclear power could be clean, safe and affordable enough to replace fossil fuels.

How did Kepco do it? The former executive who had led the bid, Lee Hee-yong, told me that the key was repetition: building the same model over and over again, rather than designing custom plants each time, which was more typical. This strategy increased experience and efficiency, and the result was lower prices. At his two-person energy consultant's office in Seoul, he told me, "Before the UAE deal, we had been building reactors continuously for the last 30 or 40 years. Having a strong supply chain and network of skilled workers was key to keeping costs so low ."

South Korea, which is about the size of Indiana, USA, eventually became the country with the most reactors in the world, with 23 reactors providing about 30% of the country's total electricity generation.

The timing of the UAE deal was propitious: France and Canada were stagnant as civilian nuclear powers, says Canadian nuclear industry veteran and Barakah project adviser Howard Neilson-Sewell. "South Korea was just about to take over the world market."

But now it's not that way anymore. Less than a decade after Barakah began construction, Korea is dismantling its nuclear industry, shutting down older reactors and scrapping plans for new ones . State-owned energy companies are switching to renewable energy. Lee's legacy has crumbled, and hopes that Seoul's nuclear program can combat climate change have been dashed to nothing.

So what went wrong? Critics blame politics, ideology and environmental idealism. In reality it was: greed, corruption and scandal. It is a reminder that the most important plans to combat climate change can fall prey to simple human venality .

disaster happened

mike mcquade

"Seeing Fukushima was a tremendous shock , especially since I live next to a nuclear power plant ," one of the country's best-known anti-nuclear activists, Kim Ik-joong, told me when we met earlier this year at a nearby coffee shop. to the headquarters of one of the most recognized civil rights groups in Seoul. Certain activists gathered near us; They were chatting animatedly, and some came over to say hello to Kim, 59. Charismatic and well-spoken, he was originally a professor of microbiology at Dongguk University, South Korea, but has become the face of the anti-nuclear movement as a prolific speaker and pundit on the nightly news.

Until the Fukushima disaster, that movement had been limited to a loose mix of local groups. The crisis in Japan brought the problem closer to home. "It just didn't seem like something that happened to other people, " says Kim.

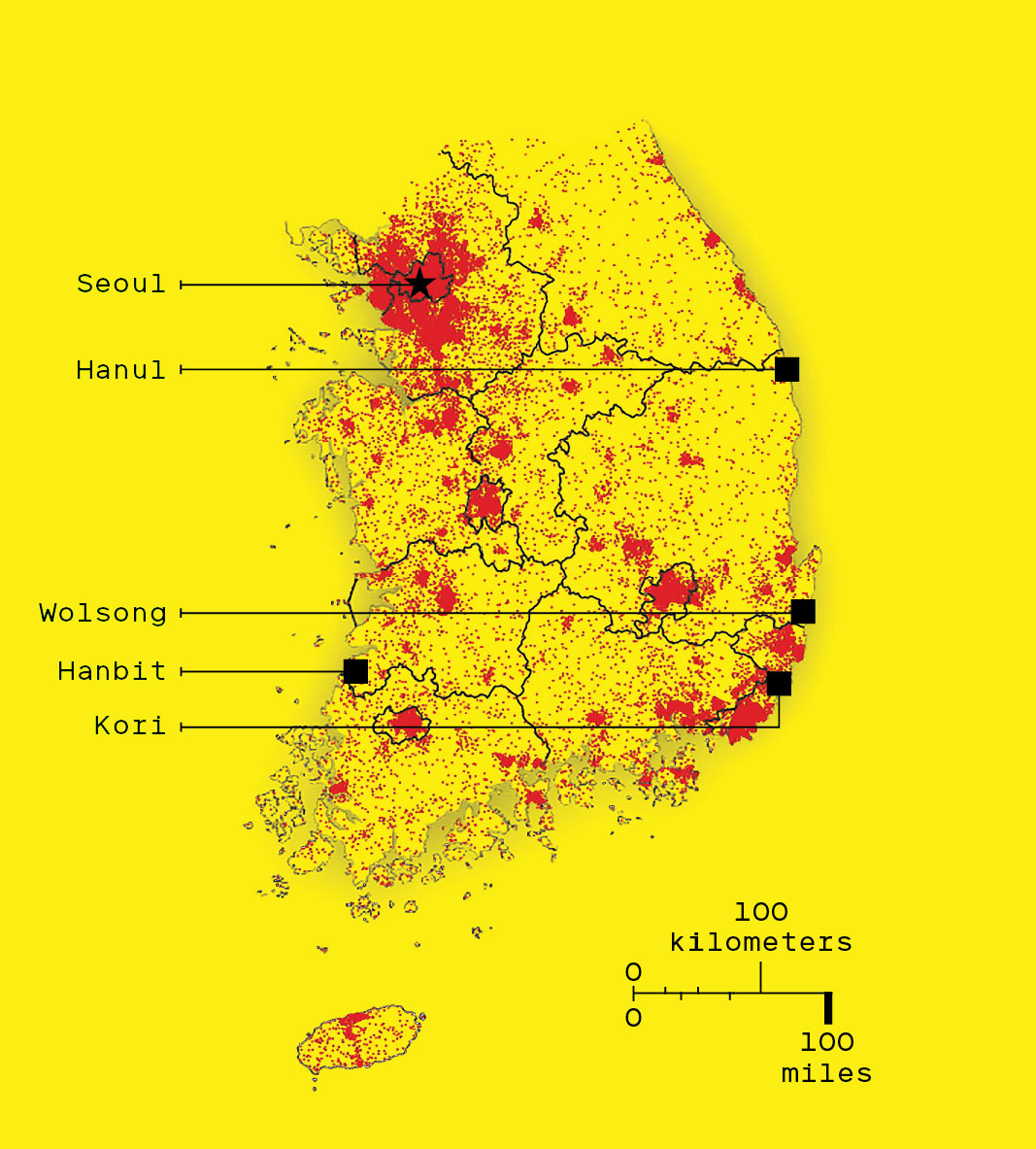

Kim did not like this overcrowding of South Korea's reactors, which are mostly clustered in a narrow strip along the densely populated southeast coast . Density was a way to reduce administration and land acquisition costs. But putting the reactors so close to each other and close to big cities was risky.

"An accident at just one of these plants would be much more devastating than Fukushima," says Kim. "These reactors are dangerously close to major industrial areas, and there are four million people living within a 30-kilometre radius of the Kori plant alone." Hyundai's car factory in Ulsan, South Korea, a city of 1.2 million, is just 20 km from the nearest nuclear power plant. Fukushima, by comparison, only had about 78,000 people living within the same distance.

Kim's cause found political support. In 2012, presidential candidate Moon Jae-in personally recruited him for his energy policy team. Moon had announced nuclear elimination shortly before as a campaign promise. Kim felt an affinity with Moon: Both of their hometowns were in the shadow of a nuclear power plant.

"He himself had done a lot of research on the subject and already had very strong personal convictions about getting out of nuclear power," recalls Kim with a smile. "Back then, there were still a lot of people in [Moon's] Democratic Party who were against a nuclear exit policy, so Moon announced it in Japan, away from anyone trying to dissuade him ."

But Moon lost the 2012 election to Lee Myung-bak's conservative successor, Park Geunhye (South Korean presidents can only serve one term). Park continued Lee's policy of nuclear expansion , pledging to increase South Korea's reactor fleet to 39 units by 2035 and make sales to potential client states such as the Czech Republic and Saudi Arabia.

However, rumors began to spread that the agreement with the United Arab Emirates had included a series of compromising clauses . The most serious accusation was that Lee had secured the project by secretly promising armed support to Abu Dhabi (United Arab Emirates) in the event of a military conflict. In 2011, South Korea began deploying special forces to the Emirates, but Lee denied any connection.

It was a sign that South Korea's nuclear success might not be just a simple story of efficiency and experience .

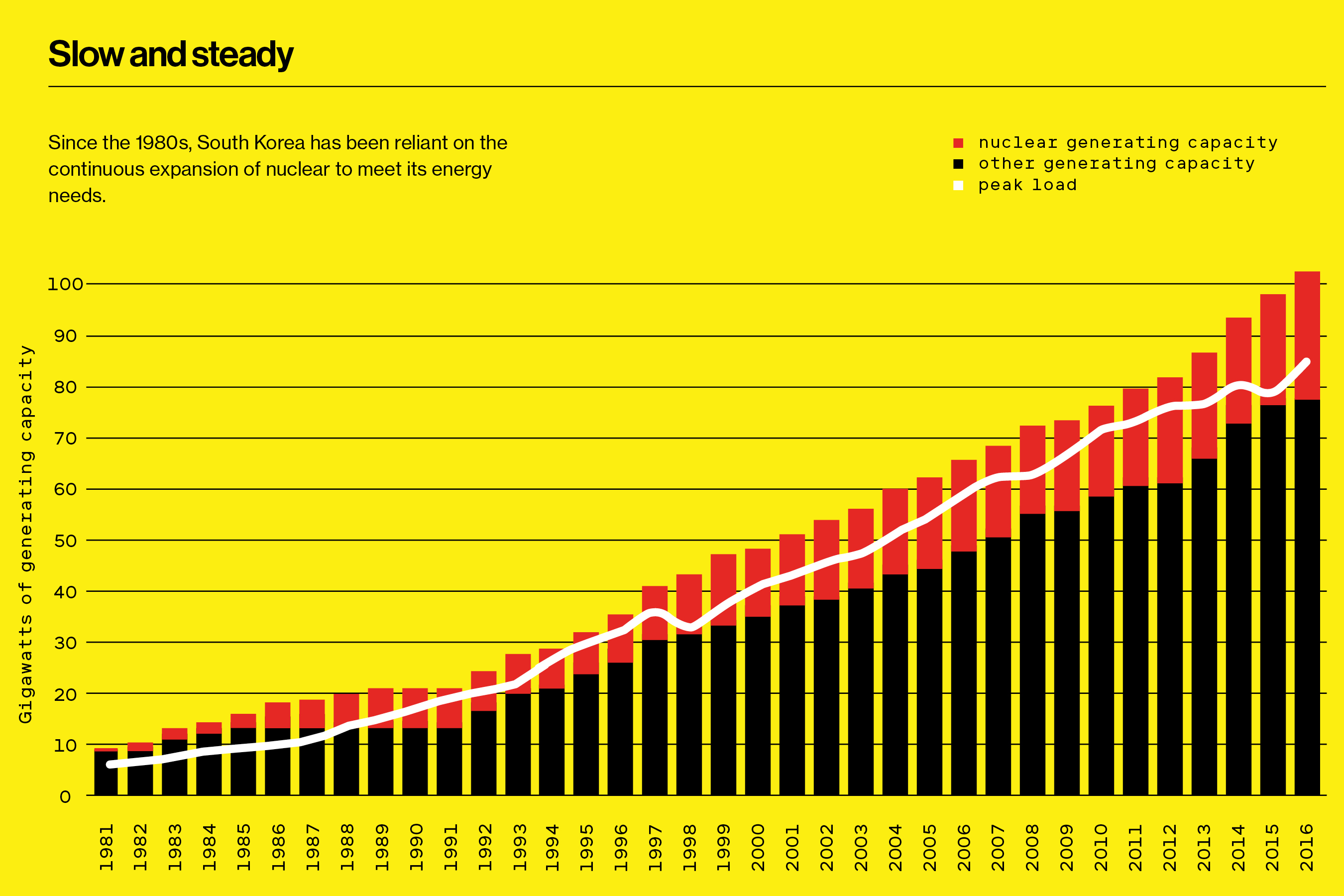

Graphic: Slowly but surely. Since the 1980s, South Korea has relied on its continued expansion of nuclear power plants to meet its energy needs. Credits: Korea Institute of Energy Economics.

Graphic: Slowly but surely. Since the 1980s, South Korea has relied on its continued expansion of nuclear power plants to meet its energy needs. Credits: Korea Institute of Energy Economics.

A shocking discovery

On September 21, 2012, KHNP officials had received an external tip about illegal activity among the company's parts suppliers. By the time President Park took office, that internal investigation had turned into a full-fledged criminal investigation. Prosecutors discovered that thousands of counterfeit parts had made their way into nuclear reactors across the country, backed by forged security documents. KHNP insisted that the reactors were still safe, but the question remained: was the real reason they were so cheap because they were defective?

Chart : Most of South Korea's nuclear reactors are clustered in its densely populated southeast . Credits : World Nuclear Association.

Chart : Most of South Korea's nuclear reactors are clustered in its densely populated southeast . Credits : World Nuclear Association.

Former manager Park Jong-woon, who worked on the reactors at Kepco and KHNP until the early 2000s, believed that was the case. He had seen that this was precisely the shortcut way in which South Korea's main reactor , the APR1400, had been built.

After the Chernobyl (Ukraine) disaster in 1986, most reactor builders had adopted a number of new safety features. KHNP followed suit, but later realized that the astronomical cost of these features would make the APR1400 too expensive to attract foreign customers .

"In the end, they eliminated most of them," says Park, who now teaches nuclear engineering at Dongguk University. "Only 10% to 20% of the original security additions were kept" .

Most important was the decision not to add an additional wall to the reactor containment building, a feature designed to increase radiation protection in the event of an accident. "They presented the APR1400 as 'new' and safer, but the so-called optimization was essentially a regression to older standards," says Park. "Because there were very few design changes compared to previous models, [KHNP] was able to build so many reactors so quickly."

By removing most of the costly additional security features, Kepco was able to drastically undermine its competition in the Emirates tender, a strategy that had not gone unnoticed. After losing Barakah to Kepco, Areva CEO Anne Lauvergeon likened the Korean project to a car with no airbag and no seat belts . When I mentioned this to Park, he sighed in agreement. "Objectively speaking, if it's twice as expensive, it's almost twice as safe," he said. But at the time, Lauvergeon's comments were dismissed as bitter words from a struggling rival.

By the time the work was completed in 2014, KHNP's internal alert had grown into a wide-ranging investigation into fraud, conspiracy and collateral fraud; in total, 68 people were convicted and the courts handed out 253 years in prison . The culprits included KHNP chairman Kim Jong-shin, the promoter of Kepco, and Chairman Lee Myung-bak's close aide Park Young-joon, whom Kim had bribed in exchange for "favorable treatment" from the Government.

Several faulty parts also found their way to Emirate power plants, infuriating Emirate officials. "It's still creating a problem to this day," Barakah's Canadian adviser Neilson-Sewell told me. "They completely lost confidence in Korea's supply chain" .

The scandals, however, were not over .

other complainant

Earlier this year, at a small bakery in Seoul, I met the former senior sales manager at Hyosung Heavy Industries, a manufacturer of jet parts, Kim Min-kyu. This skinny 44-year-old with honest, boyish eyes was the sales manager at KHNP in 2010 and quickly discovered that double dealing was as routine as paperwork .

"An accident at just one of these plants would be much more devastating than Fukushima," says Kim. "These reactors are dangerously close to major industrial areas, and there are four million people living within a 30-kilometre radius of the Kori plant alone."

"The vendors that were supposed to be competing with each other got together to decide who would win [the KHNP bids]," Kim told me. "There was a bunch of gray-haired executives from competing companies sitting across from each other, playing rock-paper-scissors to decide who would take on certain contracts ." The fictitious bids were backed by false documents, manipulated to ensure that the designated loser failed. On one occasion, he recalls, an irate KHNP procurement manager called him to point out a rookie forgery on a bogus bidding document, and demanded he do it again, correctly.

Some of these practices constituted serious security breaches. In May 2014, Kim oversaw the delivery of 11 load center transformers to the Hanul nuclear power plant in North Gyeongsang province, South Korea, but found that their security clearances had not been renewed. The load center transformers manage the flow of power for the main emergency functions in the reactors; any malfunction, Kim told me, would be "like a speeding car suddenly stopping ."

However, a secret deal between Hyosung and his competitors had designated him the winner, and the transformers were installed in two reactors, their integrity unquestioned. Frowning, Kim says, "Personally, I knew of about 300 cases where those transformers caught fire. They are very unstable. My hometown is only a few miles from those reactors, and an accident could endanger my family." relatives who live nearby .

In 2015, fearing a Fukushima-like accident, Kim decided to report corruption through his company's internal whistleblowing system. The only result was that he was fired.

With a sad smile, he remembers: "How naive I was." Finally, he went to the country's competition regulator, which referred the case to prosecutors. In 2018, he took his story to the media. A few months later, based on information from Kim, prosecutors charged six Hyosung employees and co-conspirator LS Industrial Systems with collusion, a finding Kim believes only scratches the surface of corruption.

mike mcquade

mike mcquade

More falsehoods soon came to light. In 2018, after years of government denial, former Defense Minister Kim Taeyoung admitted that rumors about the military deal with the United Arab Emirates were, in fact, true: he had overseen it himself in a desperate attempt to close the deal . Barakah. He told the South Korean media: "There was a low risk of a dangerous situation arising, and even if it did, we believed that our response could be flexible. In the event of a real conflict, I thought we would ask for a parliamentary ratification at that time".

Moon's Resurrection

In September 2016, a 5.8-magnitude earthquake (the strongest recorded tremor in South Korea's history) struck the southeastern city of Gyeongju. Anti-nuclear activist Kim Ik-joong lives in that city and recalls his surprise at the banging of windows and loud emergency sirens. He fled to a nearby rice paddy, and when he returned home several hours later, he began to feel very anxious. Gyeongju was the heart of the largest group of nuclear reactors in the world, with its own plant and two others around Busan and Ulsan. The quake confirmed Kim's fears: fault lines beneath the reactors were more earthquake-prone than previously thought . The next morning, on a visit to the nearby Wolsong power plant, officials assured Kim and his political friend Moon Jae-in that no damage had been done, but Kim could not shake the feeling that the problem was being ignored.

Critics of President Moon Jae-in have denounced nuclear elimination as ideological. But more and more South Koreans feel a mistrust of what they call "the nuclear mafia."

He recalls: "When I started campaigning against nuclear power, I was told by KHNP managers that an earthquake greater than 5.0 would never happen in South Korea, but it did." Several days after his visit to the Wolsong plant, Kim discovered that one of the plant's seismographs had been broken for years .

Although South Korean law requires seismic risk assessments of any potential reactor site before it is built, Kim believes the law's vague wording and flexible application have made it ineffective. "South Korea has not yet done a comprehensive risk assessment," he says. "Earthquake risk was not taken into account at all in the selection of the reactor site" . In fact, the first complete risk map of South Korea was started in 2017 and is not expected to be completed until 2041.

The corruption scandal and the earthquake sparked public demand for Moon Jae-in's nuclear elimination policy. But the coup de grâce came from the failures of the industry's own political champions .

Park Geun-hye's presidency collapsed in 2017, when a much larger corruption scandal was uncovered. Accused of receiving bribes from the country's major conglomerates and abusing her presidential power, she was indicted on March 10, 2017, and sentenced to 24 years in prison in April 2018. Lee Myung-bak met a similar fate a few months later. : Guilty of bribery and embezzlement, he was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Credits: International Atomic Energy Agency

Credits: International Atomic Energy Agency

Moon took office shortly after Park's ouster, and he has promptly delivered on his promise of nuclear elimination .

Kim Ik-joong explains: "The current phase-out policy stems from the four main principles we proposed at the time [in the 2012 campaign]. Older reactors would not receive life extensions; additional reactors would not be built; the use of electricity would be more efficient; and we would switch to renewable energy ."

The elimination will take 60 years. Two new reactors that were already half-finished when Moon took office are still scheduled for 2022 and 2023, and the ones that are active now will end their useful lives. In the meantime, management is still looking at potential buyers such as the Czech Republic and Saudi Arabia. But there hasn't been much progress: in fact, while Lee promised to export 80 reactors, South Korea has yet to export a single one.

Moon's critics, many of them still attached to disgraced presidents Lee and Park, have denounced the removal as "ideological," a deliberate reversal of his predecessors' achievements for political ends. However, the decline in demand for nuclear power in the country suggests a deeper disillusionment.

Kim Min-kyu, the corruption whistleblower, says: "In principle, I don't trust anything that KHNP built." More and more South Koreans feel a general mistrust of what they call "the nuclear mafia," the pro-nuclear complex that encompasses the KHNP, academia, government and money interests. Meanwhile, the government's watchdog, the Nuclear Safety and Security Commission, has been accused of revolving-door appointments, cronyism and failing to uphold the safety standards it is supposed to meet.

A decade after its inception, Lee Myung-bak's dream of South Korea's nuclear dominance appears to have finally faded. Something similar is beginning in China, until recently considered the greatest leader in nuclear energy. There, as in South Korea, Fukushima sparked public fears and forced the government to adopt stricter safety regulations, which now threaten to dramatically increase the cost of nuclear power. Of the world's other major nuclear power producers, only Russia is still aggressively building more reactors both at home and abroad. The decline of Korea's nuclear industry may have had prosaic domestic causes, but its effect in combating climate change could be quite global.