A police officer is at the crime scene of a murder. There are no witnesses or camera footage. There are no suspects or obvious motives. Just a little hair on the victim's jacket sleeve. The cells' DNA is copied and compared to a database. No match turns up, and the case goes cold.

The facial recognition subsidiary of Israeli artificial intelligence (AI) company Cortica, Corsight AI, aims to devise a solution for such a situation, using DNA to create a face model that could then be run through a facial recognition system. . But it is a task that experts in the field consider scientifically unsustainable.

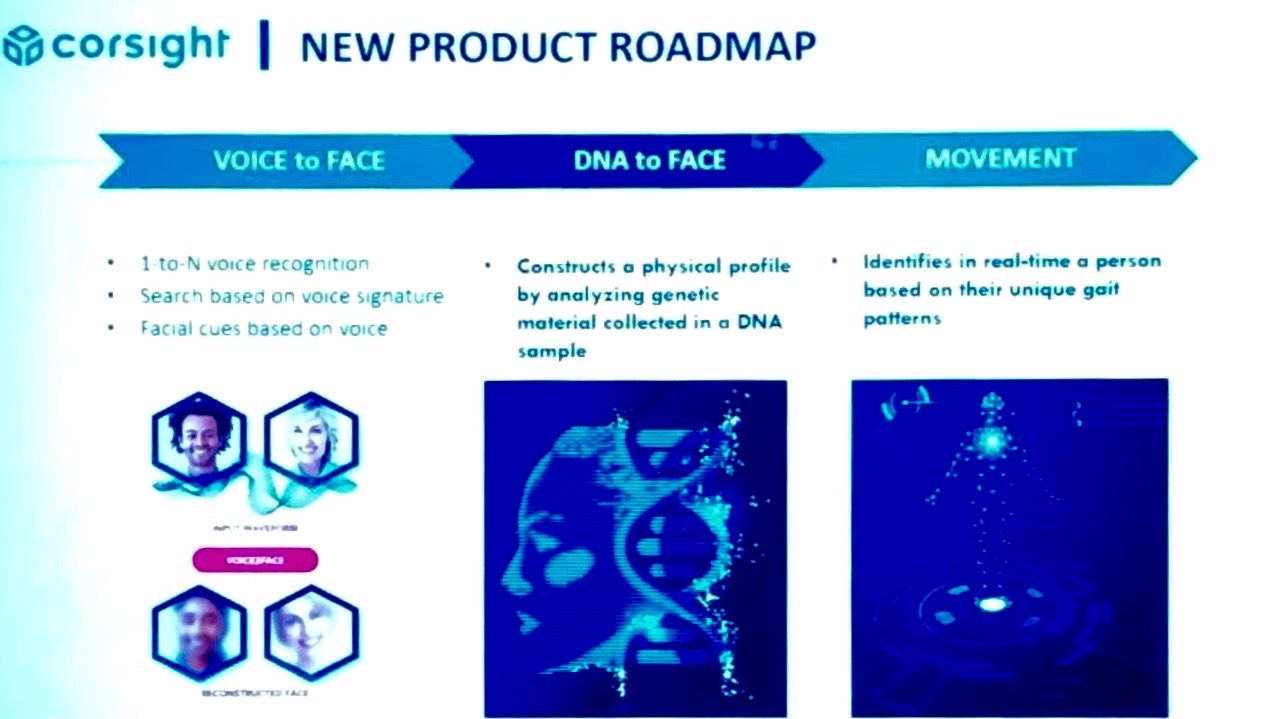

Corsight unveiled its "DNA to Face" product at a presentation by CEO Robert Watts and Executive Vice President Ofer Ronen intended to impress financiers at the Imperial Capital Investor Conference in New York City. USA) on December 15. It was part of the company's overall product roadmap, which also included motion and voice recognition. The tool "constructs a physical profile by analyzing the genetic material collected in a DNA sample," according to the company's presentation to the IPVM surveillance research group, shared with MIT Technology Review .

Photo: A photo from Corsight's investor presentation, showing its product roadmap, such as "voice to face", "DNA to face", and "motion" as an expansion of its capabilities facial recognition.

Corsight declined our request to answer questions about their product presentation and roadmap. Watts wrote in an email: "We are not contacting the press at this time as the details of what we are doing are confidential to the company."

But marketing materials show the company is focused on government and law enforcement applications of its technology . Its advisory council consists solely of former CIA Director James Woolsey and former FBI Deputy Director Oliver Revell.

However, the science to back such a system does not yet exist, and experts believe the product would intensify the bias, privacy and ethical issues already caused by facial recognition technology . More worryingly, this idea signals the industry's ambitions for the future, where face detection becomes one aspect of a broader effort to identify people by whatever means are available, including wrong.

This report has been made together with the head of IPVM operations, Don Maye, who assures that "this presentation was the first time that IPVM learned that a company was trying to commercialize a facial recognition product associated with a DNA sample ".

a checkered past

Corsight's idea is not entirely new. Human Longevity, the "genomics-based health intelligence" company founded by Silicon Valley celebrities Craig Venter and Peter Diamandis, claimed to have used DNA to predict faces in 2017. MIT Technology Review then reported that experts, by On the other hand, they had doubts. A former Human Longevity employee has claimed that the company couldn't pick a person out of the crowd using a genome, and the scientific director of genealogy platform MyHeritage, Yaniv Erlich, published a response explaining the main flaws in the research. .

Small DNA computing company Parabon NanoLabs provides law enforcement with physical representations of people derived from DNA samples through its Snapshot line of products, which includes genetic genealogy as well as 3D representations of the face. (Parabon posts some cases on its website with comparisons between photos of people authorities are interested in finding and depictions the company has generated .)

Parabon's computer generated sketches also come with a set of phenotypic characteristics, such as eye color and skin tone, which are given a confidence score. For example, a robot portrait might indicate that there is an 80% chance that the searched person has blue eyes. Forensics also modify robot portraits to create definitive facial models that incorporate descriptions of non-genetic factors , such as weight and age, wherever possible.

Parabon's website claims that its software helps solve an average of one case per week , and the company's director of bioinformatics, Ellen McRae Greytak, says they have solved more than 600 cases in the last seven years, although most are solves with genetic genealogy instead of analysis of robot portraits. Greytak notes that the company has been criticized for not publishing its proprietary methods and data, but she attributes this to a "business decision."

Parabon does not include the facial recognition AI system in its phenotyping service, and stipulates that its law enforcement clients must not use the images it generates from DNA samples as input into facial recognition systems.

Parabon's technology "doesn't indicate the exact number of millimeters between the eyes or the ratio of the eyes, nose, and mouth," says Greytak. Without that kind of precision, facial recognition algorithms can't deliver accurate results: getting DNA measurements that precise would require fundamentally new scientific discoveries, Greytak stresses, but "studies that have tried to make predictions at that level have not been successful." much success" . Greytak explains that Parabon only predicts the general shape of a person's face (although the scientific feasibility of such a prediction has also been questioned).

Police have been known to create forensic sketches based on witness descriptions via facial recognition systems. A 2019 study by Georgetown Law University's Center for Privacy and Technology found that at least half a dozen law enforcement agencies in the US "allow, if not encourage" the use of forensic sketches, either hand-drawn or computer-generated, such as photos that are fed into facial recognition systems. AI experts have warned that such a process likely leads to lower levels of accuracy .

Corsight has also been criticized in the past for exaggerating the capabilities and accuracy of its facial recognition system, which it describes as the "most ethical facial recognition system for the most challenging conditions ," according to the presentation available online. At the technology demo for IPVM last November, Corsight CEO Watts said that Corsight's facial recognition system could "identify someone with a face mask, and not just any mask, but a ski mask" . IPVM reported that using Corsight's AI on a masked face generated a confidence score of 65%, which is Corsight's measure of how likely it is that the captured face matches in its database, noting that the mask it was more accurately described as a balaclava or neck gaiter, as opposed to a ski mask, which has openings for the mouth and eyes only.

The broader problems with the accuracy of facial recognition technology have been well documented (including by the MIT Technology Review). They are strongest when photos are poorly lit or taken at extreme angles, and when subjects are darker-skinned, female, or very old or very young. Privacy and social advocates have also criticized facial recognition technology , particularly systems like Clearview AI that scour social networks as part of their matching engine.

Law enforcement's use of the technology is particularly tense: Boston, Minneapolis and San Francisco (all in the US) are among the many cities that have banned it. Amazon and Microsoft have stopped selling facial recognition products to law enforcement groups, and IBM has withdrawn its facial recognition software from the market.

"Pseudoscience"

Civil rights attorney and executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, Albert Fox Cahn, who does a lot of work on facial recognition systems, says, "I think it's ludicrous that you can to create something with the level of granularity and fidelity needed to perform facial matching . That's pseudoscience."

The researcher of the Computational Imaging Group of the national research institute for mathematics and computer science in the Netherlands Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica, Dzemila Sero, stresses that the science to support such a system is not yet sufficiently developed, at least not publicly, and that the catalog of genes needed to generate accurate representations of faces from DNA samples is currently incomplete , according to the 2017 Human Longevity study.

In addition, factors such as the environment and aging have substantial effects on faces that cannot be captured through DNA phenotyping , and research has shown that individual genes do not affect the appearance of a person's face as much as their gender. and ancestry. "Premature attempts to implement this technique would likely undermine trust and support for genomics research and would not lead to any societal benefits," Sero wrote in an email to MIT Technology Review .

Sero has studied the inverse concept of Corsight's system, 'face to DNA' instead of 'DNA to face', by comparing a set of 3D photographs with a DNA sample. In a paper published in the journal Nature, Sero and his team reported accuracy rates between 80% and 83%. However, Sero believes that prosecutors should not use his team's work as incriminating evidence and that "these methods also pose undeniable risks of greater racial inequalities in criminal justice, which warrant caution against premature application of these techniques until adequate guarantees are established.

Police forces rely on DNA data sets , predominantly from the free ancestry website GEDmatch, which was instrumental in the hunt for the notorious Golden State Killer. But even DNA sampling, once considered the only scientifically rigorous form of forensic evidence by the US National Research Council, has recently come under fire for accuracy problems.

Fox Cahn, who is currently suing the New York Police Department for records related to bias in the use of facial recognition technology, believes the impact of Corsight's hypothetical system would be disastrous. "Analyzing the impact that this is going to have, each case of facial recognition failure is magnified," says Fox Cahn. "It's easy to imagine how this could be used in really scary, Orwellian ways ."

The future of facial recognition technology

Despite these concerns, the market for facial recognition technology is growing, with companies competing for customers. Corsight is just one of several offering photo services with flashy new features, regardless of whether they've been proven to work.

Many of these new products seek to integrate facial recognition with another form of recognition. Russia-based facial recognition company NtechLab, for example, offers systems that identify people through their car license plate and facial features , and founder Artem Kuharenko explained to MIT Technology Review last year that its algorithms try to " extract as much information from the video material as possible" . In these systems, facial recognition becomes just one part of an apparatus that can identify people through a variety of techniques, merging personal information across connected databases into a kind of panoptic of data.

Corsight's system appears to be the company's foray into building a futuristic, comprehensive surveillance package that it would offer to prospective buyers. But even as the market for such technologies expands, Corsight and its ilk are at greater risk of commercializing surveillance technologies riddled with bias and error .